Ashes to ashes

We and everything we make are part of the circle of life. Everything we make will one day be composted into constituents. Even the plastics will one day, a thousand years from now, be gone. Closer to home, our neighbour Ulf passed away late April and is now back in the soil.

As mentioned last month, I have been on a journey for fifteen years now, to understand my part in the dance of elements, rain and sunshine. Said Nick Ritar inspired us to investigate how to better utilize the output of our bodies, as a source for new food. We have now two years of experience of composting the solids and diluting the liquids to utilize as nutrients for the food we grow and eat.

We are what we eat

From an atomic perspective, our bodies are built up of elements from the food we eat. The more we eat from our own place, the more important it is that the soil contains the minerals that we need.

A thought-provoking essay by the most excellent David Holmgren of permaculture fame about their health problems that came from eating only home grown food has reverberated for years. He shared a story, the gist of which was that he had been over-applying dolomite lime to their gardens, which caused a mineral imbalance that showed up as teeth problems. After thoughtful analysis, soil sampling and finally bringing in some other minerals, their own produce was again health-promoting.

In the past, many peasant populations have had mineral deficiencies from eating only "home grown" food, depending on the local soil mineral availability. Most successful cultures have included migrant species, often fish, in the diet to accumulate minerals from a larger area. In France, I have seen pigeon-towers, where pigeons could live and defecate, to bring in nutrients from a vast region to the local farmer.

Mineral deficiency does not sound nice. So, the plan was to bring in the missing nutrients in some form. But what should we get? What are we missing?

What is in our soil?

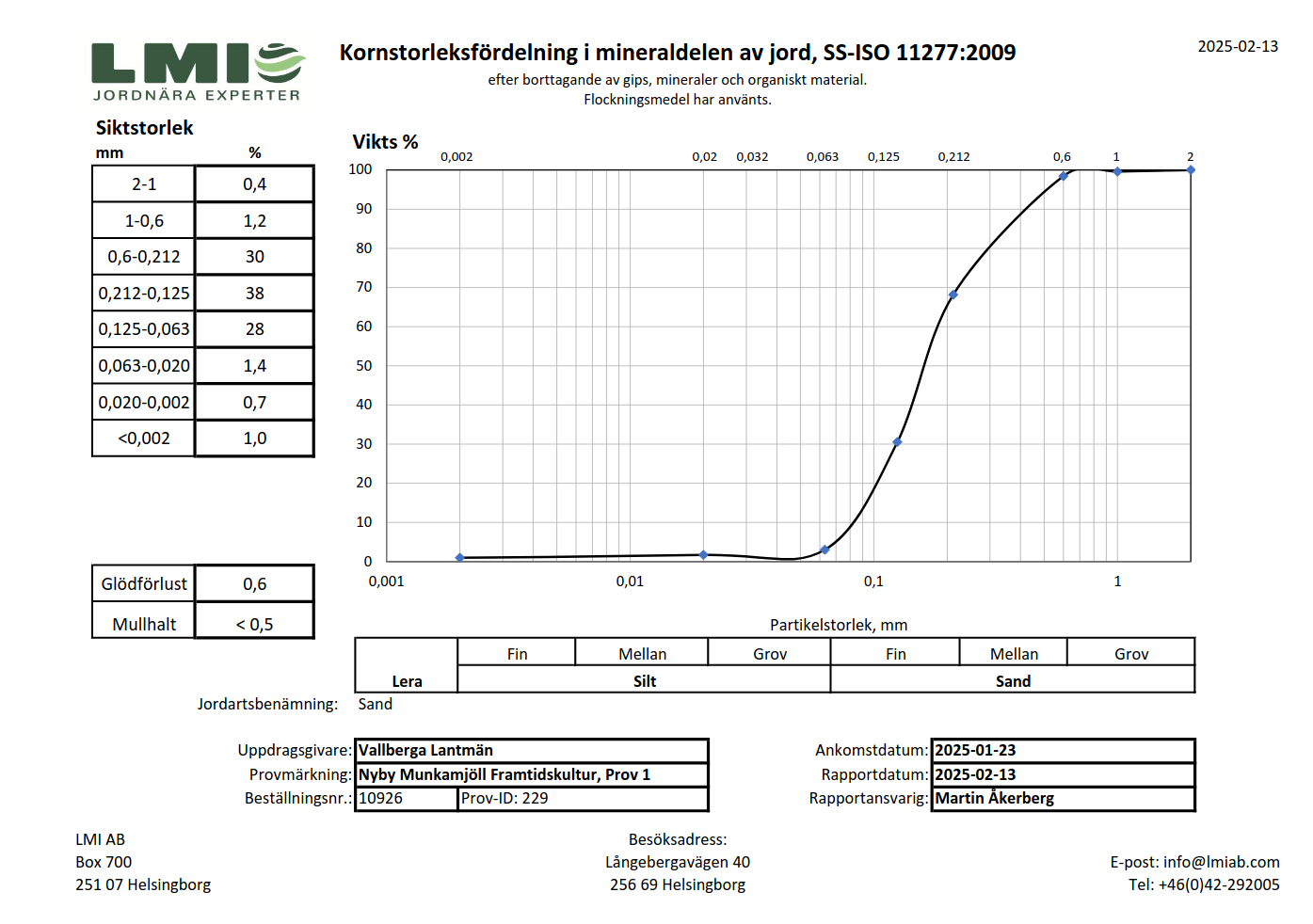

Our soil is a fine sandy soil. The main fraction is small silicate stones of 0.2mm diameter. The topsoil is varying from 15cm to 90cm in different parts of our 5000m2 farmlet. The thinnest soil is on the highest ground, and the richest soil is in the low-laying area where a stream used to run. (The rivulet was dug into a pipe in the 1960s or so.) I think that the availability of water helps to build top soil.

We sent samples of our soil to a lab to determine the nutrient content in both the top soil and in the sand below.

The first analysis was to see the soil particle size distribution. Mainly 0.1-0.5mm fine sand.

The first analysis was to see the soil particle size distribution. Mainly 0.1-0.5mm fine sand.

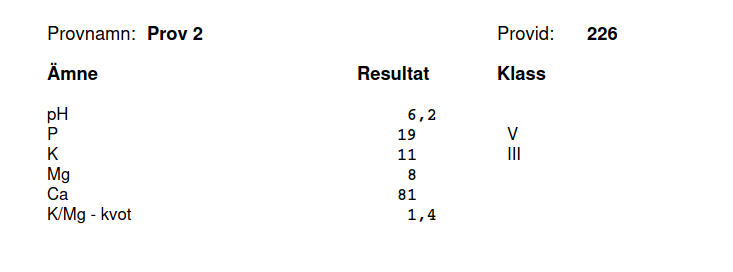

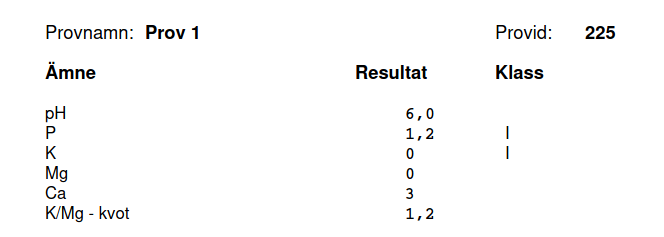

The top soil contains several water-soluble minerals, a.k.a. "spurway" analysis.

The top soil contains several water-soluble minerals, a.k.a. "spurway" analysis.

The top soil contains a little bit more of the ammoniac-leachable "albrecht" minerals, but they only check a few.

The top soil contains a little bit more of the ammoniac-leachable "albrecht" minerals, but they only check a few.

The sub soil sand contains almost nothing that the plants can absorb.

The sub soil sand contains almost nothing that the plants can absorb.

A photo from last months digging of the wetland - here is 40cm of top soil, and then yellow sand.

A photo from last months digging of the wetland - here is 40cm of top soil, and then yellow sand.

What does that mean? What should we do?

Now we have a pretty accurate number of the concentration of the minerals in the top soil, but what does it mean? What is a "good" level of manganese? Nitrogen?

I looked into the literature for tree nurseries, but found nothing. I then looked into organic vegetable growing, since vegetables for our own consumption is the highest priority product.

Organic manure is always good. We bartered two trailer loads (1000kg?) of top quality, well matured, organic cow manure from our friend Gun. That should bring a basis dose of nitrogen and phosphorus and potassium for the growing season, I thought. At least a good start.

Well-matured manure.

Well-matured manure.

To get other phosphorus and minerals, we bought a big bag of granulated blood-and-bone meal (BioFer 9-3-4+1). We plan to use it over a three year period, using 250kg every year on our 3000m2 growing areas.

Blood-and-bone-granules called BioFer.

Blood-and-bone-granules called BioFer.

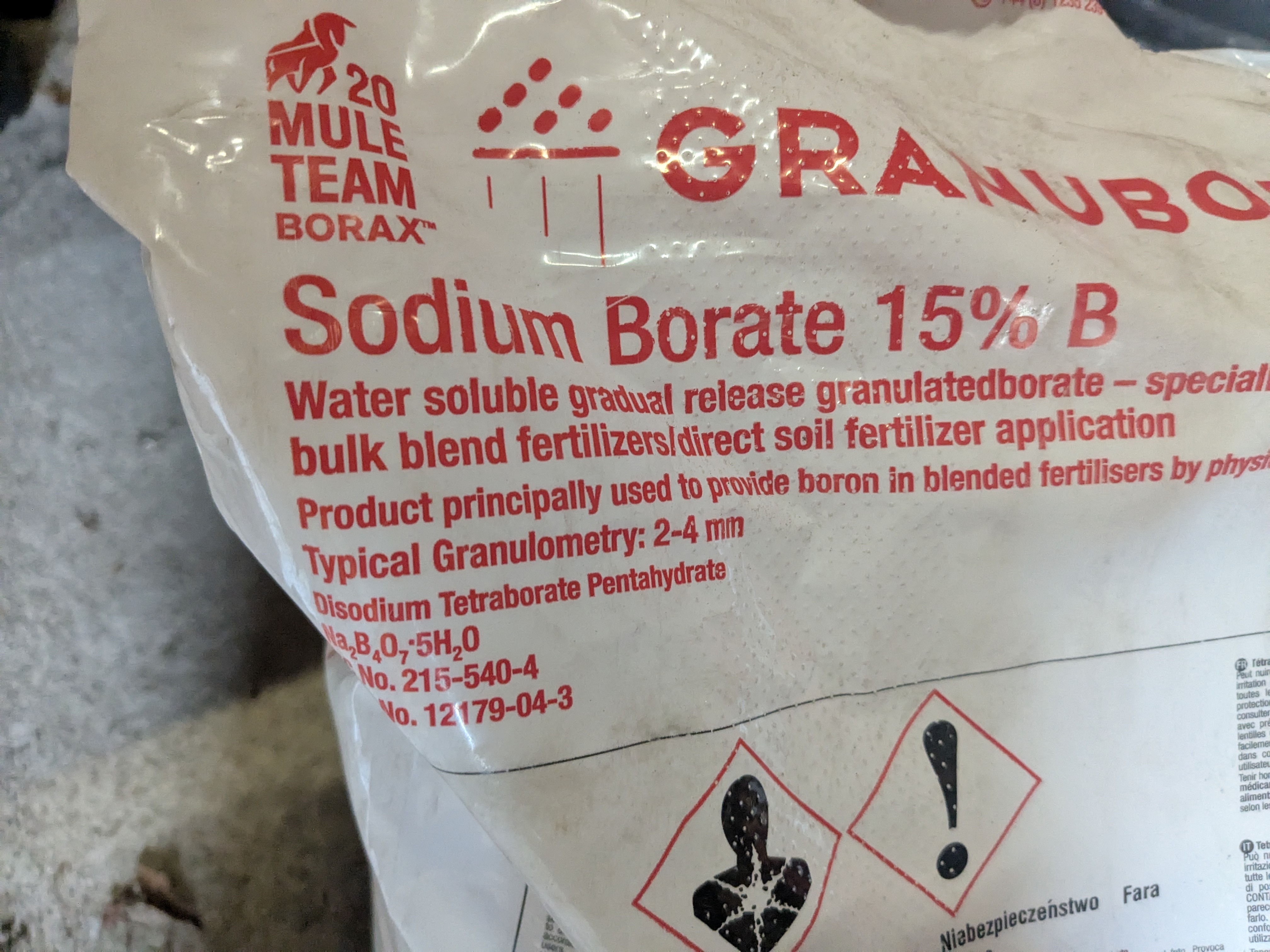

Comparing our mineral concentrations from the soil sample, with the reference, I thought that boron was the only mineral that seemed lacking. We purchased a 25kg sack of boric acid (Granubor 15% B), and it was quite expensive at 400euro.

Granubor - a boron mineral approved for organic farms.

Granubor - a boron mineral approved for organic farms.

Since we sell trees that grow out of our soils, we will lose some nutrients every year, so we need to find a way to replenish, at least the 100kg or so of tree growth that is lost. I thought that bringing in a few tons of woodchips each year would make up for the losses in the woody matter that we sell. This year we brought in another 40m3 of freshly-chipped alder. It helps to keep moisture in the ground and reduces the load of seed weeds.

We want to increase the soil carbon and depth of the top soil. The best method is to have a woodland for a century. The second best option seems to be to add biochar. During the last two years, we have used more than 1m3 per year as a soil amendment.

Two big bags with biochar.

Two big bags with biochar.

And for the permanent trees, we also use our own well-matured manure (100kg after two years?) and diluted golden liquids (400liters saved over the winter + fresh + 90% water).

The output shrinks during the composting period. After two years a whole year-production looks like 100kg.

The output shrinks during the composting period. After two years a whole year-production looks like 100kg.

It looks just like soil.

It looks just like soil.

We collect during the winter months in 3x 200liter tanks.

We collect during the winter months in 3x 200liter tanks.

We use a venturi valve to suck a 10% solution to water our permanent trees (not part of the organic nursery).

We use a venturi valve to suck a 10% solution to water our permanent trees (not part of the organic nursery).

Humanure is not approved for organic farming, so we do not use those products on the tree nursery.

We applied a lot of the nutrients during the end of May, now that we finally got some rain. For seven weeks, we had no rain. Fortunately, the weather has been cool, so the damage has been very limited.

This is what it looks like, with quite some nutrients applied.

This is what it looks like, with quite some nutrients applied.

We will apply more nutrients in June.

Nuts

We organized a nut growing course, to introduce farmers to hazelnut growing. Some were very inspired to get started, others realized that it was not the right fit for them. All got good value out of the training.

11 participants came to the one-day introduction to hazelnut farming.

11 participants came to the one-day introduction to hazelnut farming.

We have also got to know some people who have the most amazing property next to the river. We are starting a collaboration with them, to grow nuts together.

We planted three walnut trees in a field.

We planted three walnut trees in a field.

We also visited a farmer who collaborates with a company that has brought classic pulses to the Swedish food market. They have reintroduced different kinds of lentils and peas and beans, all organic.

Maybe they can process hazelnuts in their plant, and bring to the market?

Looking at dried fava beans after shelling.

Looking at dried fava beans after shelling.

Veggie news

We have good help to keep the voles at bay with our cat. He often comes to join us when we work in the garden.

Sotis is always vigilant.

Sotis is always vigilant.

We also have a kind of brown slug that is known by the name of Spanish Cannibal Slug. They came to Sweden in the 1980s and have no known enemies here. They can devastate veggie gardens. One way of collecting them is to make beer-traps. I realized that I preferred drinking the beer, so I started using sour-dough instead. The smell is attractive to the beasts and I eliminate several dozens every evening.

We also have slugs who feast on our veggies and flower beds.

We also have slugs who feast on our veggies and flower beds.

When my friend Marcel came over from the Netherlands, we fixed our pond to look a bit better.

Now it is easy to jump in, or to collect water from the pond.

Now it is easy to jump in, or to collect water from the pond.

I got to visit a tree nursery that is 100 times larger than our business. It is the largest park-tree supplier in Sweden. It was great to see how they work. I really would like to learn oculation/budding from them!

Trees of a larger size than our trees.

Trees of a larger size than our trees.

The manager was the third generation in the business, and the one who changed focus into only 5-meter-trees.

The manager was the third generation in the business, and the one who changed focus into only 5-meter-trees.

Friends

We met a lot of friends in May. We had great weather to meet up and do things together.

My friend Marcel helped to plant some new fruit trees.

My friend Marcel helped to plant some new fruit trees.

Marcel and the intern Alex helped plant out walnut trees

Marcel and the intern Alex helped plant out walnut trees

Jan-Erik showed us his yearly spring task, to re-lime the clay walls of their house.

Jan-Erik showed us his yearly spring task, to re-lime the clay walls of their house.